Safe Spaces

An article for providers on creating feelings of safety and trust.

If you work with groups of children regularly, you hold a special power in building a healthy community that includes a sense of safety for children experiencing violence in their communities. Your caring presence itself is the power, because violence—and healing from its effects—is always about the breakdown and build-up of relationships between individuals.

Grown-ups may not be able to say “I can keep you safe all the time for the rest of your life,” but you can help children feel safer, more connected, and more self-regulated in a given moment. For instance, here are some things you might say to children (perhaps in a group meeting) after a violent event in the community:

- We’re in this together.

- The bad things that happen around you are not your fault.

- All of your feelings are okay.

- When you’re in a scary situation, it’s okay to feel afraid.

- There are all kinds of feelings. Big feelings like anger, fear, and sadness are normal when something like this happens. The feelings are not bad, it’s what we do with them that matters.

- We can handle tough feelings; we can name them and then let ourselves feel them for a little while.

- There are lots of ways to help yourself when you’re having a hard time. For instance, one way to slow big feelings down is to take three deep breaths and focus on how your belly moves in and out.

- Bad things happen, but there are always people who are trying to help.

Using a trauma-informed lens in your work benefits everyone, because trauma-informed practices even benefit those who have not experienced trauma. You might start by building your understanding of the chronic stress that children living with the threat of violence experience, and how it can lead to the misunderstanding of social cues. For instance, children who have witnessed or experienced violence are more likely to interpret others’ actions as hostile because of the way they “scan the world.” A child may feel threatened by a teacher’s raised voice even if the teacher is not necessarily angry. Or a child may misunderstand a peer who is approaching quickly simply because they want to play, and respond with fear or aggression.

In addition, behavior problems such as poor impulse control, biting, kicking, and hitting may be an effect of children witnessing or living with violence. Feeling a pervasive sense of danger hinders self-regulation skills, and children lack the coping strategies necessary to positively manage their emotions and behaviors.

You can model healthy social-emotional skills in everyday moments. For instance, when you’re frustrated, you can narrate how you stay calm: “I’m so frustrated I need to take a time out/take three deep breaths.” You’ll be demonstrating how to handle tough emotions, rather than teaching that tough emotions are bad.

When you hear sirens outside, you can model empathy, compassion, and hope by reframing the experience for yourself and for children by saying: “Let’s close our eyes and send good wishes to whoever is hurt or in danger.”

Children may feel powerless in the face of the challenges in their community, but you can remind them that when they are kind to others, when they share, take turns, and use words for their feelings, they are making our world safer and more peaceful.

Trauma and the Body

An article on the effects of violence on children.

Using These Resources: Violence

Article about the Sesame Street Community & Gun Violence initiative.

We’re Not Alone

A music video on the power of community connections.

1, 2, 3, Color Me

Sitting quietly and coloring together is a stress-reliever for adults and children alike.

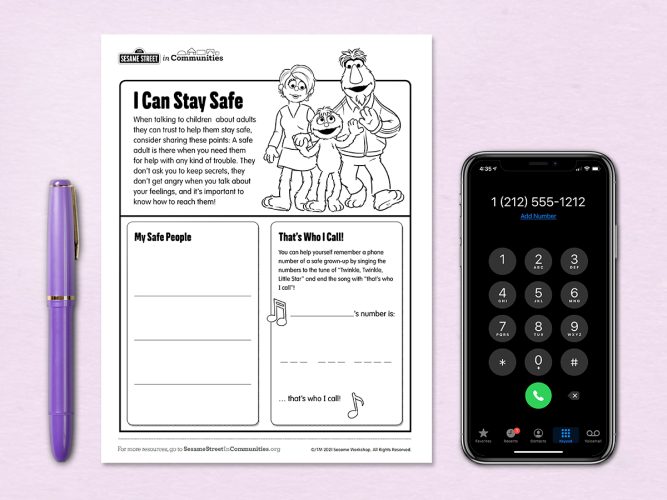

I Can Stay Safe

It’s important for children to know several people they can turn to when something goes wrong.

I Don’t Want to Live on the Moon

A song about the power of human connections.

Community Conversation: Community Violence

Many communities are unfortunately impacted by community violence, but there are people and organizations striving to help. You can, too!