Remote ECD services require a unique focus on three aspects of program design: creating awareness of the program and tools, encouraging utilization, and maintaining participation and engagement.

When the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020, Play to Learn had to adapt or replace in-person services with remote services across Bangladesh, Lebanon, and Jordan, navigating each country’s pandemic restrictions. From 2021 to 2023, Play to Learn worked with partners at the University of Virginia (UVA) Humanitarian Collaborative to document and review lessons learned about the design and delivery of remote ECD services. This webpage shares the principles and lessons from UVA’s research and highlights the ways in which Play to Learn programs applied these principles.

Remote ECD services can serve multiple purposes:

- A supplement to in-person programming providing additional activities and/or opportunities to practice and reinforce skills.

- An extension to reach people who lack reliable access to in-person services, like those living in remote areas or with disabilities.

- A temporary replacement, providing alternative services in situations where conflict or crisis disrupts in-person service provision.

Examples of programs that supplemented, extended, or temporarily replaced in-person ECD programs.

Semillas de Apego Program

Video context viewed by children and caregivers at home provided a supplement to an in-person program in Colombia.

Remote Early Learning Program

A fully remote program extended services to children in remote areas of Lebanon.

Pashe Achhi Program

A remote program provided a temporary replacement for in-person ECD services during the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh.

Gindegi Goron Program

An extension.

Delivery Approaches

ECD content can be delivered remotely using a variety of mechanisms and devices and can target different audiences – children, caregivers, teachers, facilitators, or a combination of these – and may be directed to individuals or small groups.

Individual use

Digital content is provided to an individual for independent access on a device. This is appropriate when children and/or caregivers have access to devices, are open to using them for educational purposes, and have sufficient digital literacy.

Facilitated use in group settings

This is appropriate for children with limited access to devices at home and/or when caregivers are not familiar with using devices for educational purposes.

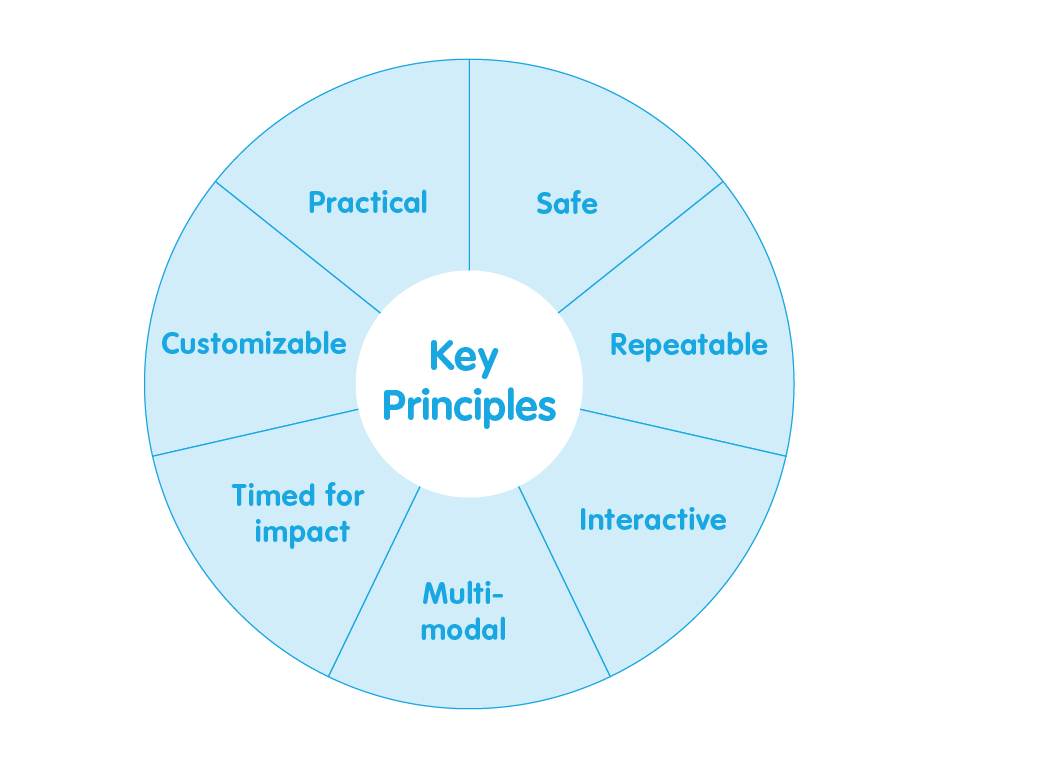

Key Principles for Design

Regardless of the purpose, device, and content, effective remote or hybrid ECD programs must balance the following design and implementation principles in order to drive consistent engagement and impact.

1. Practical: To facilitate equitable access, build on participants’ existing device access, digital and media practices, and digital literacy skills – and provide necessary technology if needed. Also, make remote services as simple and easy to understand and use given the challenges marginalized individuals face, including daily demands, cognitive load, etc. Play to Learn spent significant time prototyping or piloting all programs, including remote or hybrid programs. Take a look at how the Gindegi Goron program piloted and prototyped the technology to ensure that the platform, messages, and activities suited Rohingya families.

2. Customizable: Tailoring information and activities to participants’ needs (i.e., culture, age, ability, etc.) makes services more accessible and relatable and translates into participation and impact. The Pashe Achhi program developed new content from scratch to ensure that activities and messages could be feasibly delivered over the phone.

3. Interactive: Building interaction into the service—both in terms of interaction via the device and promoting caregiver-child interaction—can help children engage and maintain interest. It can also help caregivers get the most value and remain involved. The Remote Early Learning Program in Lebanon held virtual “classes” with caregivers to promote strong relationships between facilitators and caregivers, as well as individualized follow up calls to caregivers.

4. Repeatable: One of the benefits of remote approaches is that users can access information and activities repeatedly. Consistent repetition helps learners build and reinforce knowledge and promotes behavior change. In the Semillas de Apego program, viewing videos numerous times helped children in Colombia.

5. Multi-modal: An informed combination of no-tech, low-tech, and high-tech approaches can ensure that programming is accessible to all children and caregivers. A multi-modal approach can also provide for different learning styles and thereby improve outcomes. This diversity of approaches can simultaneously engage younger and older siblings present in a single household. The Remote Early Learning Program used multiple modalities to deliver content and reach families: print materials for at-home use, WhatsApp for facilitators to communicate with caregivers; and phone calls to deliver individualized sessions or follow-up calls.

6. Timed for impact: Remote ECD programs should fit into caregivers’ schedules. For example, parenting support works best when caregivers have the time and attention to engage with the lesson (such as on weekends, after school, after a meal, etc.), so identifying and targeting these windows can maximize impact. Timing is essential when there is intermittent internet or electricity for participants. Programs delivered via phone in Bangladesh, like Pashe Achhi or Gindegi Goron, similarly had to time live and automated calls according to when male heads of household would be at home, so that messages and activities could be delivered to their wives and mothers too.

7. Safe: It is critical to ensure data privacy and guard against cyberbullying, online exploitation, harmful content, and inappropriate data collection or use.

Challenges to Access

Obstacles to access vary by population and region. In the Play to Learn program, in Cox’s Bazar, internet connectivity and smartphones are not available to Rohingya living inside the camps. In Lebanon, Jordan, and Colombia, barriers also included the cost of smartphones or data packages; lack of or inconsistent electricity and/or internet; and, in some cases, low digital literacy. Play to Learn programs addressed these barriers by providing pre-loaded devices, subsidizing or paying for data plans or devices, and using applications that do not require an internet connection or large data plans.