What Mental Health Specialists Want Parents to Know About Anxiety

An article for parents about childhood anxiety

Anxiety can look very different from child to child. Common signs include trouble sleeping, complaining about stomachaches or other physical symptoms, avoiding certain situations, becoming more clingy, trouble concentrating, or tantrums.

We spoke to four child mental health providers, Devika Bhushan, MD, Christine Crawford, MD, Neha Navsaria, PhD, and Marian Williams, PhD, about childhood anxiety. Here’s what they told us.

What is anxiety?

Bhushan: Fear and worry are part and parcel of being a human. That’s how our brain lets us know something isn’t safe; something needs our attention, or we need to prepare. And that’s all very normal. Behavioral and mental health concerns are on the rise. When a parent notices changes in their child’s behavior, sleep patterns, energy levels, or school performance, it often indicates stress. The task is to sort out these symptoms, starting with the parent’s gut feeling. And we rule out physical causes first.

Williams: Anxiety can start early. For instance, many children have separation anxiety. We generally don’t diagnose a serious problem in these earliest years. For little ones, anxiety can be a normal part of figuring out, you know, who’s mom, who’s safe, you know?

When parents are concerned about children’s anxiety, what’s important for them to remember?

Williams: With anxiety, it’s usually it’s a relief to be able to say, okay, this is a recognizable condition and it is treatable, right? We have a name for it. We have a protocol for it and we have things that we can try and each person and each family situation is unique. We individualize the recommendations and care as much as possible, but remember that this is something that many, many, many people have dealt with. Up to one in five children will develop an anxiety disorder! And so it’s really helpful I think for people to understand that this is not something that’s unique to their child, and that it is recognizable and treatable.

Bhushan: Parents often feel relief when they know a condition is treatable, but they may also feel self-blame. It’s crucial to understand that anxiety, and all mental health challenges are not anyone’s fault. They result from a complex interplay of genes, biology, experience, and environment. Every mental health condition is treatable, and it’s important to seek help and support.

Any mental health condition is as easy and likely to become treated and stay in remission as a physical health condition, and I think that even though we know less about the brain and we can predict with less accuracy which kids will do well with what kind of therapy or medication, we know that we have a number of tools to help kids when they when they have a mental health condition. Every single mental health condition is 100% treatable, which is not to say that it’s going to be in remission for the duration of someone’s life, but that it is able to be treated as any physical condition.

While parents often feel relief to know that this is something nameable and treatable, they’re often feel guilt or blame themselves. And I think that’s because of the stigma around so many of these conditions where it becomes a shaming and blaming narrative of “well, this wouldn’t have happened to my child or in my family if it wasn’t for me having done X, Y, or Z, and me being a less good parent than I could have been.” And the truth is, nobody’s ever going to be a perfect parent!

When should I be concerned?

Bhushan: When children are separated from a caregiver that they know and trust, some distress is normal. So are tantrums, they’re part of the toddler years, that’s children learning to really work through a stressful moment. It gets to be worrisome when the overwhelming feelings last hours instead of minutes. It gets worrisome when it really impacts their ability to sleep, to go to daycare or school to function normally.

If anxiety is related to a transition which will pass, like separating from a parent or caregiver, there are specific coping skills to help with that. Other times it’s something more involved, like perhaps there’s been a traumatic experience that the parents may not know about or that they do know about and that it’s going to be a longer lasting set of stressors that that kid needs to work through. And in those circumstances, we can do more.

So the question really becomes when does that fear and anxiety or worry get out of proportion to this stress or the exposure? And when does it start to interfere with someone’s life? And by the time somebody is actually coming in for care for this, they’ve recognized that it is something unusual enough to merit additional support.

What should all parents keep in mind, whether or not they’re concerned about anxiety?

Crawford: As early as you can, start to have conversations with children about their emotional well-being. You can constantly build emotional literacy, name the feelings, talk about feelings so that you don’t find yourself in a situation in which you’re constantly in the dark, feeling like there’s so many unknowns about your child’s mental health because they don’t know how to talk about it. Young children haven’t had the opportunities as they develop the language to talk about their emotional state. They haven’t had the practice, so you want to provide them with as many opportunities to practice talking about their emotions. Don’t just save it for during a time of crisis or during a time when you are concerned.

Williams: I think that there’s such a tendency to over program and block off time for different kinds of activities throughout the weekend or evenings. The value and the time for unstructured play and connection, which is so critical in terms of strengthening that parent-child relationship and that bond, but also spurring that creative, imaginative self confidence. That really comes from unstructured play! And so I think creating that space for unstructured together time, it’s really important.

Spending time in nature together, walking, playing games, cooking together, making a craft that might be different or fun or unusual, reading together, watching funny movies, or just making funny faces, having interpretive dance parties, whatever it is, where everybody is having true fun… all are so good for our stress response systems! We’re winding back all of physical impacts of stress, and it really puts kids and adults in a very different frame of mind.

Navsaria: I want to mention the concept of reframing. I always say to parents that it’s one of the biggest superpowers that we often don’t know we have. If we don’t reframe, we stay stuck. Reframing doesn’t mean that you’re minimizing what’s going on. But you’re taking a child who’s having any kind of big feeling or big behavior that goes along with it and you’re reframing it to understand that they have a need at that point. Without reframing, it’s very easy to feel defeated and manipulated, like children are just pressing our buttons. I definitely validate parents for feeling that way! But reframing opens you up to solutions: What is my child’s need in this moment? What is my role in helping them get to that need? That it opens it up.

Crawford: I think it’s really important for parents and caregivers to know that kids are always watching them as the model for how to navigate stress and intense feelings. So when we pay attention to our own mental health, including managing our own anxiety, we’re helping them too. And so when we’re thinking about improving the health and well-being of our children, we as adults have to improve our own health and well-being too!

Devika Bhushan MD is a pediatrician, public health leader, and author. She serves on the Board of Directors for the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) and is Chief Medical Officer of Daybreak Health.

Christine Crawford MD is associate medical director at NAMI. She is adult and child psychiatrist based in Boston and is an Assistant Professor of Psychiatry at Boston University School of Medicine.

Marian Williams PhD is a licensed psychologist with 20 years of experience at Children’s Hospital, Los Angeles (CHLA). She specializes in infant-family and early childhood mental health and developmental disabilities in children.

Neha Navsaria PhD is a clinical psychologist and Associate Professor of Psychiatry in the Division on Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. She is also Co-director of the preschool mental health clinic at the school.

Special thanks to our content partners at American Psychological Association and National Alliance on Mental Illness.

We’re Learning as We Go

Watch this video and discover habits to support your family’s digital well-being.

Episode 1 - Ask an Expert: Choices

In the first episode of this six-part series, hear from an expert about how daily decision-making plays a role in family digital well-being.

Watch and Play: Abby's Magical Beasties

Watch this episode and explore ways to extend the learning at home.

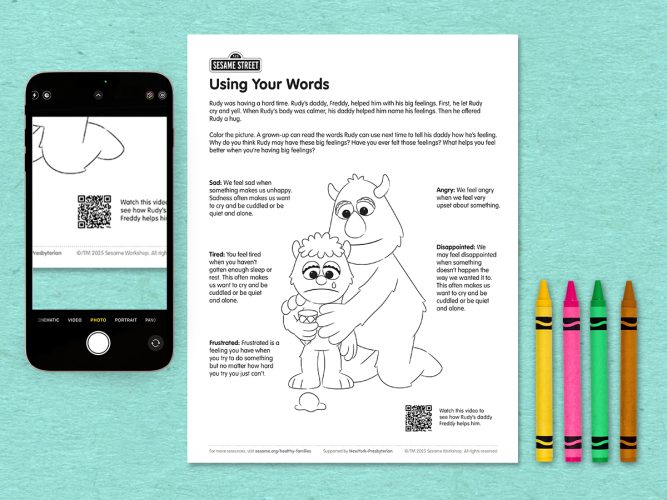

Using Your Words

A coloring page helping children explore words for big feelings.

C is for Choices

Elmo and Louie make choices on how and when to use technology as a family.

C is for Choice

A game about making choices, big and small.

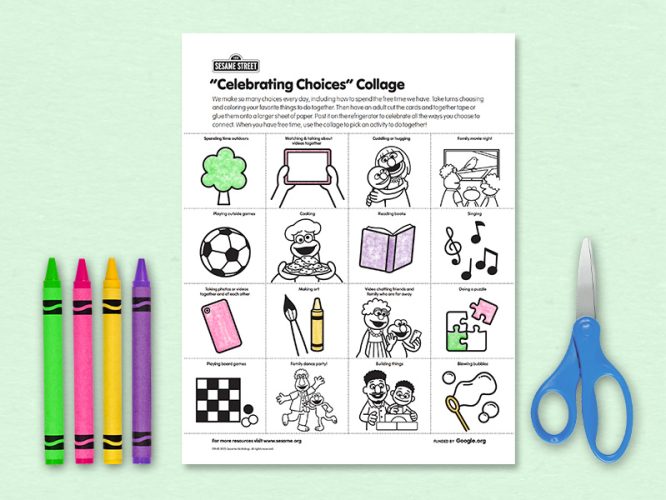

“Celebrating Choices” Collage

Celebrate the ways you choose to spend time together as a family!